The reading balance model was proposed 30 years ago when neuropsychological research used to focus on hemispheric lateralization. According to the theory on the function of brain hemispheres, spoken and written language is controlled by the left hemisphere, while visual-spatial perception is controlled by the right hemisphere. However, it was soon discovered that the rules of spoken language are processed by the right rather than the left hemisphere (Bakker & Robertson, 2002).

According to neuropsychologists, dyslexia is caused by a disorder in the structure of brain hemispheres. Based on Bakker's (2002) reading balance model, dyslexia is caused by dysfunctions in both hemispheres when reading. According to this model, reading is mainly done by the right hemisphere in the preliminary stages but by the left hemisphere in advanced stages. At the beginning of reading, the brain must analyze the written word in terms of its spatial form, and then perceive this spatial form with its appropriate sound and meaning (Lorso et al., 2011). In perceptual dyslexia, one reads correctly but very slowly (left hemisphere), whereas in linguistic dyslexia, one reads quickly but incorrectly (right hemisphere) (Bakker, 1990).

Bakker treated dyslexia through neural stimulation of brain hemispheres (HSS-HAS), and many researchers achieved promising results with this method (Licht & Bakker, 2005; Goldstein, 2001; Robertson, 2002; Faham, Ahmadi, Ashayeri, & Ashtari, 2017; Hamedi, 2012).

According to Bakker (1992, 2002), preliminary reading requires a perceptual analysis of the form and direction of letters and words. This perceptual analysis is performed by the right hemisphere. A child in first grade encounters a large number of letter forms that do not follow the principle of object permanence. Object permanence means that objects and shapes retain their meanings independently of their spatial position. If we rotate a cup 180 degrees, it is still a cup; but if we rotate letter d 180 degrees, it will become letter p. Similar semantic changes are observed in many other letters (t, f, b, y, w, m, u, n). The novice reader faces other problems, too. If we change the shape of a clay cup, it may become a different object, like a hat or a saucer. Changing the shape of d to D, however, does not change its meaning. Shifting the sequence of letters in a word alters the meaning of that word (amen, mane, name, mean); still, MEAN, mean, and Mean all have the same meaning. The order of the words from left to right is also important in the meaning of the sentence: He is at home. Is he at home? At home he is.

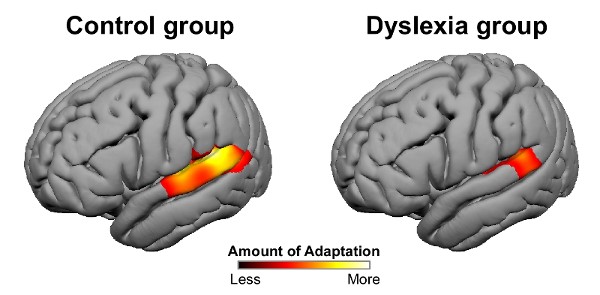

The analysis of these perceptual features and the direction of the text mainly stimulates right hemisphere processing. Therefore, at first, the hemispheric balance of control in reading tends to the right; that is, in preliminary reading, the balance of reading control tends to the right hemisphere, whereas in advanced stages, the balance of reading control tends to the left hemisphere. If this hypothesis is true, we must observe a shift from the right to the left hemisphere in the process of learning how to read. To test this hypothesis, a study was conducted for four years on preschool children who could not read (Leach, 1988; Bakker, 1992). First, a number of words were instructed to five preschoolers. After the children mastered the words, the words were presented at the center of their visual field. Brain responses (word-related potentials) were recorded during the word presentation. These responses were recorded from the temporal and parietal areas of both hemispheres for four consecutive years.

In the first and second years, the amplitude of the temporal region of the right hemisphere was larger than that of the left hemisphere due to the presentation of words. In the third and fourth years, however, the amplitude of the temporal region of the left hemisphere was larger than that of the right hemisphere. No such shift was observed in the control group. As such, these changes may be due to the presentation of words to the hemispheres. Based on the analysis of WRP and the scores of multiple reading and spelling tests, it was concluded that reading and spelling processing might be associated with right hemisphere activity in the first two years but with left hemisphere activity in the final two years. Thus, in the process of learning to read, the shift from the right to the left hemisphere occurs by the end of first grade or the beginning of second grade (Bakker, 1992).

According to Bakker's reading balance model (2002), when learning how to read, some children cannot transition from the right to the left hemisphere. These children read slowly, intermittently, and accurately, and lack fluidity in reading. Bakker describes this group of children as dyslexic type P due to their over-reliance on the perceptual features of the text. In some other children, the left hemisphere plays a key role as soon as they start the process of learning to read. These children try to take advantage of linguistic strategies related to the left hemisphere, and so they ignore the perceptual features of the text, which leads to fast and careless reading. Bakker classified this group of children as dyslexic type L.

Translated by Dr. Shirin Mohamadzadeh